How to Blow Up Your AEM Project in 5 Easy Steps

Paul Legan, March 7, 2016

Nobody likes an Adobe Experience Manager project gone bad. We know this first hand because we’ve jumped into the middle of more than our fair share of slow-motion AEM train wrecks.

In this Expert Talk we explore some of the ways companies inadvertently derail their deployment of AEM, and provide tips on how you can avoid being one of them.

[Excerpt from Video Transcription]

Jess Moore: Thanks everyone for joining this 3|SHARE Expert Talk Series. This month's topic is How to Blow Up Your AEM Project in Five Easy Steps. My name's Jess Moore and I'm the CEO and co-founder at 3|SHARE.

Incidentally, this is one of the highest attended Expert Talks yet. I suspect that's because this hits a nerve in all of us because the failure and success of an AEM project, pound for pound, has more of an impact on your brands and your business than almost any other technical initiative that you could undertake.

A successful launch of AEM will take you and your company to staggering heights and will create a massive improvement in your ability to market to your customers and potential customers. While a failure, because of the different types of things that it touches, will turn heads so high on the food chain, you will have the undivided attention of the C-Suite, in not the good way, who will want to know exactly what went wrong, and ultimately how to avoid that again.

Before we get into the bulk of the presentation, a little about us. We're digital marketing experts focused 100% on the Adobe Marketing Cloud. Within the marketing cloud, the vast majority of our business revolves around training, consulting and managed services for AEM sites, assets and apps.

We're a 3|SHARE Day Software Partner. That's to say that when Adobe acquired Day Software, and CQ, now AEM, we came along with that acquisition. So we've been working with this product since 2001.

We have all the top-level badging that you would expect from an expert on AEM, including specializations. We're a top-level solution partner, founding member of the Adobe Partner Advisory Board. Last year, we were acquired by Publicis Group, because we're recognized as the top AEM specialist in the world.

The majority of our workforce is in the U.S., scattered throughout the U.S. About a third of our company is based in Argentina. At 85 people, we may seem small, but we are actually a veritable giant in the AEM space. You'd be hard-pressed to find another company in the world that could put 85 seasoned, trained AEM experts with multiple projects under their belt into a single room.

So I thought we'd start with some of the macro level project stuff, more or less just kind of fun facts, before we dive into the top five things that are guaranteed to blow up your AEM project. I'm sure most of you are familiar with the Chaos Report by the Standish Group. And for those of you who don't know, it's a study that's focused on project success rates. It started in 1994, and it is probably the most widely cited research on project success rates and best practices in the world.

From a 2015 report, 19% of all IT projects will fail in 2015, so that's 1 in 5. The nice thing is, since they've started reporting in 1994, it's gotten better, 31% of projects in 1994 they found were cancelled before they finished. They found that the number one reason for project failure is size and complexity. These are the most important factors in project success.

Speaking of project success, I'd like to welcome Mr. Paul Legan who will show you exactly what not to do when you're implementing your AEM project.

Paul Legan: Thanks again everyone for joining. Let's get right into it. Number five on our list of ways to successfully blow up your AEM project is to deprioritize or de-stress training throughout the entire process. I can't even convey how important training is, especially in the beginning of a project.

#5: Deprioritize Training

Oftentimes when education is an afterthought, or worse, if knowledge is assumed on either side of a conversation, you introduce a gap between what is said and what is meant. And that kind of comes to a head in terms of the initial information gathering phase of a project. Usually this is right at the beginning, and this is a critical point in an AEM project.

It starts with one group of people knowing a lot about AEM, and one group of people knowing not as much about AEM. And this introduces sort of a defensiveness and an indecisiveness on functionality. And without that clear direction on where to go, especially when you're trying to lock down actual functionality for a year or two-year project, this becomes more and more important.

Sharing knowledge introduces a comfort zone among all parties. The main point of this in an initial part of a project is that first kickoff meeting which is very important because an AEM project has a lot of different people involved in different roles. Due to that large audience, there will, no doubt about it, be a meeting where you have attendees that are a mixture of non-technical and technical people. And that's why establishing a baseline of understanding, again, enables decisiveness across departments and roles.

It's also important to understand that learning is essentially decoding. The amount of jargon that I've probably used over the years, and I've definitely heard others use, is extraordinary and what it encodes the information that we're really trying to dispel. Many times you'll be in a meeting when people do not know what you're talking about. You're either using jargon or you're trying to solve a problem technically without first understanding everything completely. You're not providing tools for an audience to actually decode the information they're hearing, so it's lost.

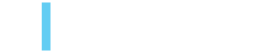

When, in an AEM project, should you introduce training? This is a sort of a trick question, because honestly, the earliest that you can introduce training and the number of times that you can do it over the course of a project really determines the success. Our practice at initial kickoff meetings is to produce product demos for every single piece of functionality that a client has purchased and has shown desire to use.

During the actual requirement sessions, we'll go through actual functionality that pertains to every single piece of functionality that started the project off in the first place. This is very important for especially authors, because authors and authoring experience is so critical to the adoption of the CMS in general, but AEM more specifically.

As we move through the project we take a sort of a waterfall-agile hybrid approach to our development, but we do incorporate sprints. And during these sprints, we provide a demo that is not only just a demo, but it's an engaging Q&A session. The idea is that people will be in the product, and we will have trained actual users on every piece of functionality that we've developed at each sprint level.

Not all training needs to be formal, where you take four hours of your day and you actually deliver a training to a group of people. A lot of times it's the reinforcement of those things. I like to think of it sort of as homework. So after I give a sprint demo, I very much like to have a takeaway, or notes, distribution or a worksheet that goes with the demo to make sure that everyone understands exactly what we've done, and what their role is on testing, and also providing feedback in the best way possible.

When you embed education and training throughout the entire project timeline, which you can do without extending the timeline, you get more decisive feedback, and these decisions often invest users into the actual product.

That said, if you prefer no clear direction, and you are genuinely looking to blow up your AEM project, then deprioritizing training is possibly the best way to go.

#4: Forego Transparency

The next thing that is essentially another great way to ensure an unsuccessful project is to forego transparency. Transparency is something that's very important to organizations and very important, I think, in any project. And by that, I mean that at any stage of the project, it's very important to actually be aware of what you've done and what you haven't done, and convey that to stakeholders.

Honesty in demos goes an extremely long way. Some tips that we generally like to convey are to use annotations to actually show which pieces of functionality are not ready for testing in a negative point. We also like to provide agendas before each demo, that way people can follow along. And we set expectations for exactly what's not working.

It becomes very clear later on, after a demo, which pieces of functionality you're actively trying to avoid at any given point. And so we like to avoid all that and just be very honest with what we've done, and what bugs exist, and what things are still left to be done.

One of the first projects I was on with 3|SHARE was with ASICS America on their digital asset management project. I was fortunate enough to follow the project along to Japan and to Australia. And one of the first meetings that I had in Japan was a status report meeting where the stakeholder in Japan looked at our status report and said, "Wow, that is a lot of red."

In that moment I was somewhat freaking out. I thought this was going to be a big deal, but the reality is that people really appreciate when others are honest and open about what is going on in a project, especially when they're spending a lot of money to implement something that impacts a lot of people.

And so what I've learned is that just because there's a lot of red on a status report, but there's a plan to mitigate all that red and turn it back to green, that it's a conversation that needs to be had, and often results in even more rapport between two people. Because again, no one likes to be swindled, and this is critical to the success of an AEM project

#3 – Embrace Bureaucratic Inertia

So if you're not already on your way to an awful project, the next step would be to completely and utterly embrace bureaucratic inertia. And what bureaucratic inertia is to me, it's the fact that in general, everything that happens on a project, everything that we do, always takes longer than we anticipate. This could be accessing a VPN or accessing specific servers or installing servers or converting HTML templates to AEM templates. These are the things that are always road-blocking the beginning of a project.

But I think the critical thing to understand is that this is always the case, and things always take longer than we anticipate. And it's not something that we can't anticipate in general through proactivity.

A lot of times, we talk about proactivity as being something that is the ideal state, but if you've been on several AEM projects, you've seen that there are logical streams of development that can be completed in parallel. And if a road block prevents one track from moving forward, there's always an opportunity to switch to the other one.

I look to Disney to provide guidance or innovation here, because Disney is the undisputed leader in queue psychology. So if you've ever been to a Disney property, you've probably waited in line for a long time, but you've probably waited in line for slightly less time than you thought you'd have to wait in line.

Disney executives have clearly understood that people get angry when they wait in line for a long time, and they've decided to jerry-rig the system such that people feel like they're waiting in line for a lot less time. Again, this is kind of like the things like the performers that walk through lines, and the wait times shown actually being longer than they are. So Disney took a proactive approach to a very common issue throughout all of their properties.

And you can do the same in AEM. One of the key indicators of an unsuccessful project are when we have designs that have not yet been finalized. And by designs, I mean actual desktop and mobile and tablet designs that are still in process as we start a project. This is something that you can generally avoid by mandating it as part of the design of a project plan.

The second thing you can do is request all system access for all potential resources on day one. It should be the first meeting invite that you send out, and that way you ensure that everything will take much longer, but of course, if you start earlier, then maybe you can mitigate that.

And lastly, it's very important to utilize progressive development for the components. When you're developing a site and you have only static HTML, let's say, it's important to give that visual as part of a demo or as part of a training, and then essentially take that static content and make it dynamic through the use of dialogues and editing controls, etc. But it's, I think, critical to the success of a project to show that progression from static content to dynamic, and iterating, as you do.

#2 – Don’t Respond, React

We've all had a situation where we've reacted instead of responded. And by that, I mean that we've not taken a second to think about what we're about to say before we handle a situation. And this is an absolute sure-fire way to make sure things do not run smoothly.

I think of a classic story here about a child who has broken a valuable. And as a parent, you immediately react by getting angry or perhaps yelling or upsetting the child and yourself. And this worsens the relationship between you and your child, but it also doesn't make anything better.

But if you notice your reaction as anger, and you pause, and you take a breath, and you consider everything, you're first response really is to see if your child's okay, and if they're hurt or scared. And then you realize that the object is broken, it's no longer there. And you calmly talk about how you can avoid this mistake in the future. This is a situation that really focuses on the pause.

The pause, there are a ton of situations within AEM in which you have the opportunity to react poorly, specifically around discussing additional scope in future sprints or performance issues or bugs and demo expectations. These are probably the three most prevalent areas where you're bound to have an awkward conversation or two.

And if you react to something poorly in a meeting with a lot of people, you lose a little bit of rapport. And building it up again and maintaining it after that is much more difficult. Again, this is true of any project, but it's especially true of a project that has so many different players.

So how can we avoid that? Well, I think in general, illustrating and being able to explain yourself in most situations is critical. And each role on a project, whether you're a developer or a project manager or anyone else on the project, has specific things that they can do.

As a developer, you should always be able to explain your reasoning behind a specific code decision or pattern. It's really critical that when you're challenged, you don't take that challenge defensively, but you present an argument about why you feel you did what you did. And oftentimes this is received much better than expected.

As a project manager, you can be strategic about enhancements, and you collaborate with the architect at all times to establish the impact. And by that, I mean a lot of times, there's a disconnect between, and you add additional scope that may not take that long, versus something that may impact significant other development that's already been going on. So it's important that a project manager and a development team are always on the same page in assessing that impact.

And then for everyone, mistakes will always be made. There will always be scope that's overcommitted or overcommitting to scope. And there will always be a development task that takes longer or needs to be refactored because new information came later on. But it's most important to learn from each of these tasks and move on to the next, because there's really nothing else we can do.

Many projects that I've seen personally that have gone south have been in one meeting, you can usually point to a meeting or two meetings where there is a lot of negativity based on a decision that was made, either based on an assumption or based on simply just poor decision. And these are things that you can very easily avoid as part of a multi-month project.

#1: Introduce Complexity

But the single best way to kill an AEM project is to completely introduce complexity. Complexity is probably the killer of more projects, especially software, than I've seen any other thing take responsibility for. If you've heard of Rube Goldberg, which I'm sure you have, then you understand what I mean.

Oftentimes when you're hired to work on an AEM project, you're considered an expert or a subject matter expert. And it's often easy to associate complexity with cleverness. And as an expert, you need to define a solution or architect a grand solution to a problem that may not require a grand solution. And this is really important to understand as a solution partner.

There are some pretty robust frameworks that Adobe has provided within AEM, and adding value doesn't always mean creating new functionality. It might mean extending something that's there, or utilizing something that's there and focusing your effort on something else. This has been true on a lot of our projects, especially more recently, where we try and drill home the fact that user experience, especially for authors, is generally the best investment you can make as part of a AEM project.

Oftentimes we recommend that you skip the custom user experience changes or core product overlays, and use more of the budget on an offering experience. In other words, don't reinvent the wheel. Use the wheel. Use as much of the wheel as possible and use it for as many purposes as you can.

But even going further, there's some aspects from a more technical perspective that you can use to ensure that you're not introducing complexity. Oftentimes as a developer, you get caught up in what exactly you're doing in that one task, and you're not able to see all the tasks around you. So enforcing coding standards that make onboarding straightforward and attractive is very important.

And by that, I mean as you add resources to a project, it shouldn't be extremely difficult to get a new person up to speed, especially when there are such modular components within AEM that you can utilize, expand upon for a common library across projects, or across projects within a specific environment.

Encouraging developers to peer-review code before formal code reviews is also really, really important. Peer reviews, a second set of eyes, is probably some of the best advice. And this is very true in terms of complexity.

There was one time early on in my career where I spent the better part of a month essentially creating my own inherited paragraph system, which comes with AEM. I wasn't fully informed about what needed to be done and what was there for me. And this is something I had to learn the hard way by eating pizza at 2 a.m., trying to figure out how Adobe already did something.

And finally, in terms of complexity, in college, one of my professors as a freshman told me something that I never forgot. He said that you should never let edge cases win. And by that, I think he meant that there are always going to be the 0.1% of a project where you are looking at something that only happens once a year or only needs to happen once a day, and you let that dominate your strategy for implementation.

And this gets in the way of utilizing common libraries and utilizing the frameworks that Adobe provides. And it also tanks budgets and tanks rapport when you're talking about conveying delays in a project to an end user or to a stakeholder. So I would say that edge cases in general and complexity can, by far, tank a project more than any other piece of a timeline or project.

CONCLUSION:

In summary, deprioritizing training, foregoing transparency, embracing bureaucratic inertia, reacting without responding, and introducing complexity are the five ways that will make someone not want to work with you ever again on an AEM project.

So on behalf of everybody here at 3|SHARE, thanks for attending and have a great week. Please download the entire presentation or contact us with any questions you may have.

Topics: Adobe Experience Manager, Digital Marketing, Professional IT Consulting Services, Webinars